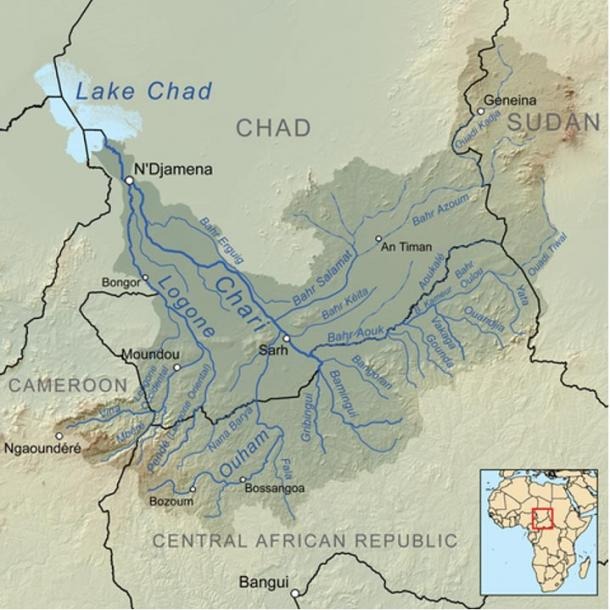

The Sao civilization was an ancient culture located in Central Africa, in an area which is today partly owned by the countries of Cameroon and Chad. They settled along the Chari River, which is located to the south of Lake Chad.

The modern Kotoko people, an ethnic group located in Cameroon, Chad, and Nigeria, claim ethnic descent from the ancient Sao. According to their tradition, the Sao were a race of giants that used to inhabit the area to the south of Lake Chad, between the northern regions of both Nigeria and Cameroon.

Sparse written records of the Sao

The term ‘Sao’ was likely to have first been introduced into the written sources during the 16th century AD. In his two chronicles (both of which were written in Arabic), The Book of the Bornu Wars and The Book of the Kanem Wars, the grand Imam of the Bornu Empire, Ahmad Ibn Furtu, described the military expeditions of his king, Idris Alooma.

Those populations that were conquered and vanquished by Idris Alooma were generally referred to as the ‘Sao’, the ‘others’ who did not speak the Kanuri language (a Nilo-Saharan language).

These settlers, who were possibly the first settlers of the region, spoke one or another Chadic language, derived from the evolution of the Central Chadic language sub-family.

A hierarchical social structure and the conquering Bornu State

The works of Ibn Furtu also provide some information about the way that the Sao were organized. Apart from evidence suggesting they were structured into patrilineal clans, it is said that the Sao were organized into ranked and centralized societies, thus indicating a hierarchy. These polities were either called chiefdoms or kingdoms, depending on the circumstances.

In addition, the Sao were recorded to have dwelt in small towns that were protected by moats and earthen ramparts, thus suggesting that they may have functioned as city-states.

When Idris Alooma conducted his military campaigns, the towns of the Sao that were closest to the Bornu heartland were conquered and absorbed into the Bornu state. Those on the outer periphery, however, were more difficult to rule directly, and a different strategy was employed.

Instead of conquering these towns, they were coerced into a tributary status, and a representative of the Bornu state-appointed in residence to oversee the local government. Therefore another explanation for the decline of the Sao may be through assimilation.

An ethnographer and fascinating art

Although Ibn Furtu has provided some knowledge of the last days of the Sao, the origins of these people were not touched upon by this chronicler. It was only during the 20th century that archaeologists sought to answer this question.

One of these archaeologists was Marcel Griaule, the leader of the French Dakar-Djibouti Expedition (1931-1933). As an ethnographer, Griaule was fascinated by the folk traditions of the peoples inhabiting the Chadic plain and collected their oral lore. These were then translated and published as Les Sao Legendaires.

It was due to this book that the concept of ‘Sao Civilization’ or ‘Sao Culture’ was coined and popularized. This idea of ‘culture’ was manifested in the works of art produced by its people. Therefore, Griaule’s expedition was concerned mainly with finding pieces of art produced by the Sao.

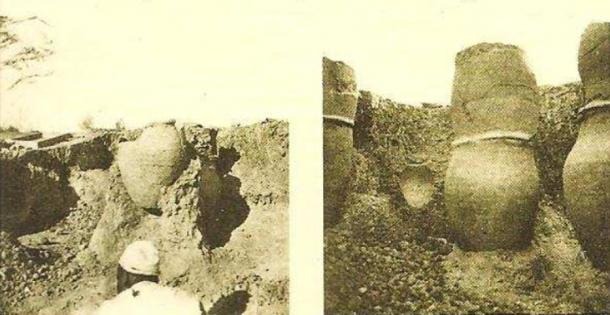

Griaule was not disappointed, as the Sao produced intriguing statuary in clay, large, well-fired ceramic vessels, and fine personal ornaments in clay, copper, iron, alloyed copper and brass (see featured image).

By using the archaeological data, Griaule was able to support ethnohistorical scenarios that already discussed the Sao’s achievement. These ethnohistorical scenarios were also used to interpret the archaeological evidence.

This circular approach claimed that migrations were the engine of cultural change, and did little to aid our understanding of the origins and evolution of the ‘Sao Civilization’.

Funerary practices of the Sao

Archaeological evidence shows that the Sao buried their dead. The tradition of placing a corpse in the fetal position inside of an earthenware jar was in practice from the 12-13th centuries AD. The funerary jar was closed by placing another jar or a small ovoid pot on top. However, this tradition was abandoned by the 15th century when simple burials became the norm.

New excavations create a Sao timeline and are categorized

A more scientific approach was employed in the 1960s during the excavation of Mdaga, and the concept of a ‘Sao Civilization’ based on artwork was dropped. The results of the excavation showed that Mdaga was occupied from around 450 BC to 1800 AD.

It was impossible to consider such a long period of occupation under the heading of ‘Sao Civilization’, and the findings from Mdaga were thus accompanied by excavations at Sou Blame Radjil. The Sao civilization was found to be not truly one group, but composed of many societies that lived in the Lake Chad region.

Nevertheless, old habits die hard, and the term ‘Sao Civilization’ is still used today, with its period of existence commonly given as ‘the late 6th century BC to the 16th century AD.’

In total, there are more than 350 Sao archaeological sites thought to be present within Chad and Cameroon. Most of the sites that have been discovered are composed of artificial long or circular mounds.

The archaeologist and ethnologist, Jean Paul Lebeuf, categorized the Sao sites he studied into three types. Those of Sao 1 are said to be small, low mounds that were used as places of worship or rituals. Small figurines are found at these sites.

Sao 2 sites consisted of large mounds that had walls. They were the burial sites and many figurines are associated with these locations. Finally, Sao 3 sites are thought to be the most recent and have produced few, if any, significant finds.

Whilst there have been many past discoveries of Sao statuettes and art pieces, there is still a lack of information on the history of this complex ancient civilization.