Among the list of the hottest places on Earth, the Sahara desert in Mauritania, Africa definitely figures in the lineup, where temperatures can reach as high as 57.7 degrees Celsius. Harsh and hot winds ravage the extensive area throughout the year but there is also a mystery place in the desert; and worldwide, it is known as the ‘Eye of the Sahara.’

The ‘Eye of the Sahara’ – the Richat Structure

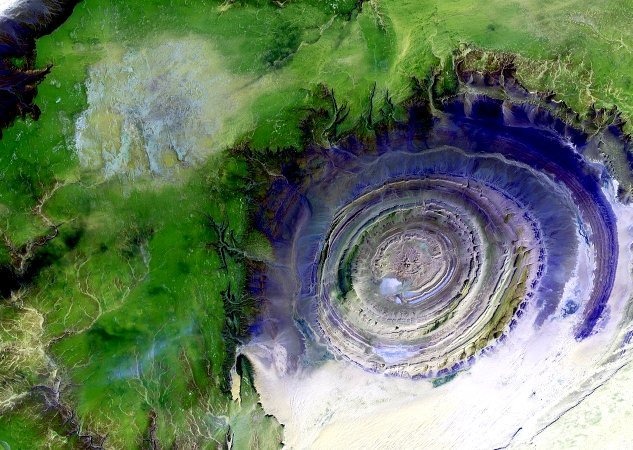

The Richat Structure, or more commonly known as the ‘Eye of the Sahara’, is a geologic dome — though it’s still controversial — containing rocks that predate the appearance of life on Earth. The Eye resembles a blue bullseye and is located in Western Sahara. Most of the geologists believe that the Eye’s formation began when the supercontinent Pangaea started to pull apart.

Discovery of the ‘Eye of the Sahara’

For centuries, only a few local nomadic tribes knew about this incredible formation. It was first photographed in the 1960s by the Project Gemini astronauts, who used it as a landmark to track the progress of their landing sequences. Later, the Landsat satellite took additional images and provided information about the size, height, and extent of the formation.

Geologists originally believed that the ‘Eye of the Sahara’ was an impact crater created when an object from space slammed into the surface of Earth. However, lengthy studies of the rocks inside the structure show that its origins are entirely Earth-based.

Structural details of the ‘Eye of the Sahara’

The ‘Eye of the Sahara’, or formally known as the Richat Structure, is a highly symmetrical, slightly elliptical, deeply eroded dome with a diameter of 25 miles. The sedimentary rock exposed in this dome ranges in age from Late Proterozoic within the center of the dome to Ordovician sandstone around its edges. Differential erosion of resistant layers of quartzite has created high-relief circular cuestas. Its center consists of a siliceous breccia covering an area that is at least 19 miles in diameter.

Exposed within the interior of the Richat Structure are a variety of intrusive and extrusive igneous rocks. They include rhyolitic volcanic rocks, gabbros, carbonatites and kimberlites. The rhyolitic rocks consist of lava flows and hydrothermally altered tuffaceous rocks that are part of two distinct eruptive centers, which are interpreted to be the eroded remains of two maars.

According to field mapping and aeromagnetic data, the gabbroic rocks form two concentric ring dikes. The inner ring dike is about 20 metres in width and lies about 3 kilometres from the centre of the Richat Structure. The outer ring dike is about 50 metres in width and lies about 7 to 8 kilometres from the center of this structure.

Thirty-two carbonatite dikes and sills have been mapped within the Richat Structure. The dikes are generally about 300 metres long and typically 1 to 4 metre wide. They consist of massive carbonatites that are mostly devoid of vesicles. The carbonatite rocks have been dated as having cooled between 94 and 104 million years ago.

Mystery behind the origin of the ‘Eye of the Sahara’

The Richat Structure was first described in between the 1930s and 1940s, as Richât Crater or Richât buttonhole. In 1948, Richard-Molard considered it to be the result of a laccolithic thrust. Later its origin was briefly considered as an impact structure. But a closer study in between 1950s and 1960s suggested that it was formed by terrestrial processes.

However, after extensive field and laboratory studies in the late 1960s, no credible evidence has been found for shock metamorphism or any type of deformation indicative of a hypervelocity extraterrestrial impact.

While coesite, a form of silicon dioxide considered as an indicator of shock metamorphism, had initially been reported as being present in rock samples collected from the Richat Structure, further analysis of rock samples concluded that barite had been misidentified as coesite.

Work on dating the structure was done in the 1990s. Renewed study of the formation of the Richat Structure by Matton et Al from 2005 to 2008 confirmed the conclusion that it is indeed not an impact structure.

A 2011 multi-analytical study on the Richat megabreccias concluded that carbonates within the silica-rich megabreccias were created by low-temperature hydrothermal waters, and that the structure requires special protection and further investigation of its origin.

A convincing theory of origin of the ‘Eye of the Sahara’

Scientists still have questions about the Eye of the Sahara, but two Canadian geologists have a working theory about its origins.

They think that the Eye’s formation began more than 100 million years ago, as the supercontinent Pangaea was ripped apart by plate tectonics and what are now Africa and South America were being torn away from each other.

Molten rock pushed up toward the surface but didn’t make it all the way, creating a dome of rock layers, like a very large pimple. This also created fault lines circling and crossing the Eye. The molten rock also dissolved limestone near the center of the Eye, which collapsed to form a special type of rock called breccia.

A little after 100 million years ago, the Eye erupted violently. That collapsed the bubble partway, and erosion did the rest of the work to create the Eye of the Sahara that we know today. The rings are made of different types of rock that erode at different speeds. The paler circle near the center of the Eye is volcanic rock created during that explosion.

The ‘Eye of the Sahara’ – a landmark from space

Modern astronauts are fond of the Eye because so much of the Sahara Desert is an unbroken sea of sand. The blue Eye is one of the few breaks in the monotony that is visible from space, and now it’s become a key landmark for them.

The ‘Eye of the Sahara’ is a great place to visit

Western Sahara no longer has the temperate conditions that existed during the Eye’s formation. However, it is still possible to visit the dry, sandy desert that the Eye of the Sahara calls home—but it’s not a luxurious trip. Travellers must first gain access to a Mauritanian visa and find a local sponsor.

Once admitted, tourists are advised to make local travel arrangements. Some entrepreneurs offer airplane rides or hot air balloon trips over the Eye, giving visitors a bird’s-eye view. The Eye is located near the town of Ouadane, which is a car ride away from the structure, and there is even a hotel inside the Eye.