The remains were thought to belong to a couple until DNA analysis revealed that they were a Roman-era mother and daughter from the second or third century C.E.

More than a thousand years ago, two people were laid to rest in what is now Wels, Austria. Though their remains were discovered in 2004, it’s only recently that they’ve been identified as a mother and daughter.

This extraordinary find represents a first for Austria, and offers a unique look at what life was like for ancient Romans living in the country some 1,700 years ago.

Uncovering The Mother-Daughter Grave In Austria

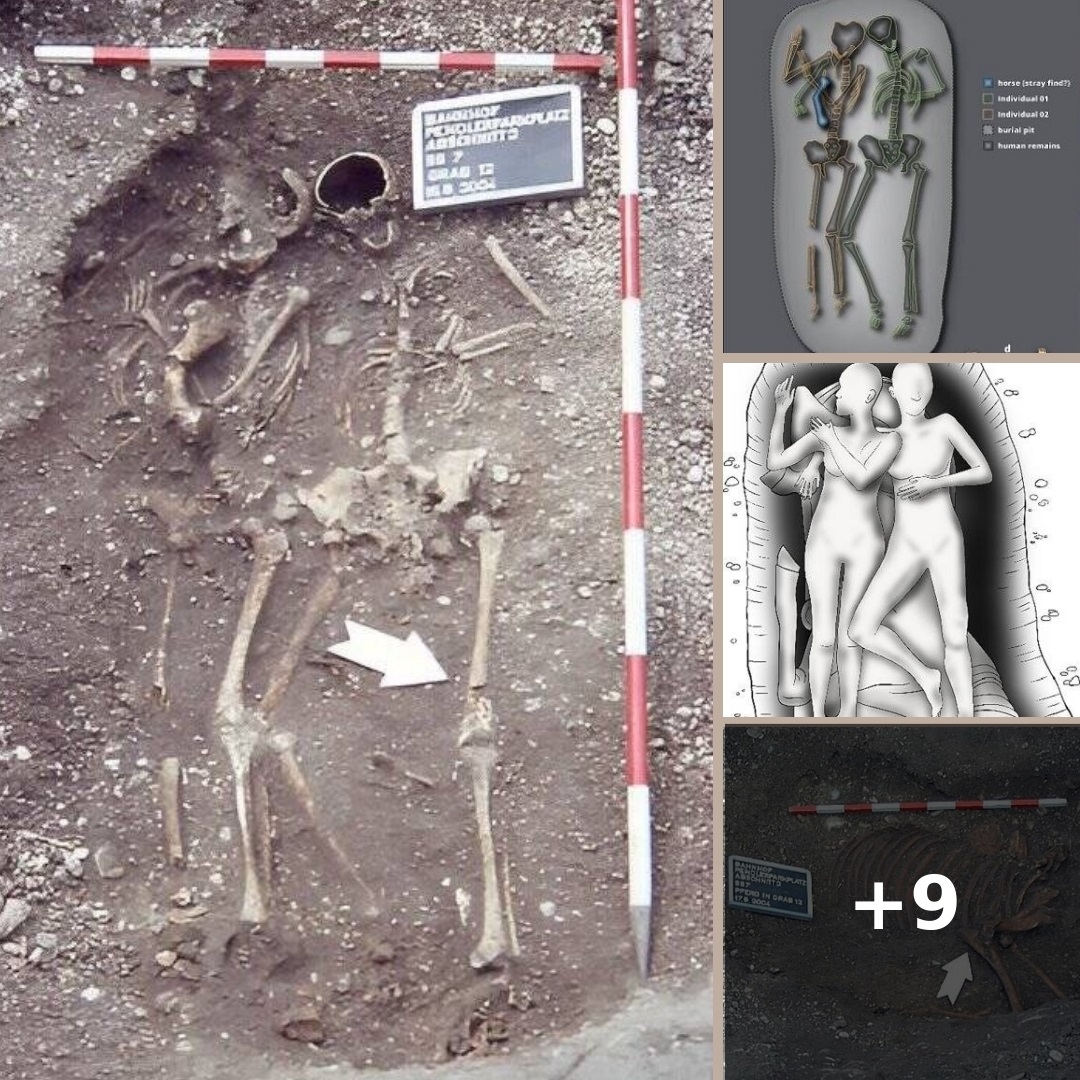

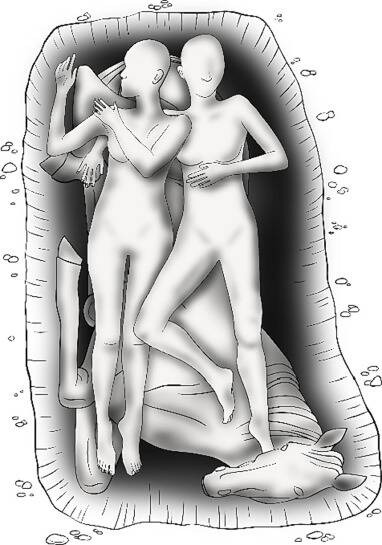

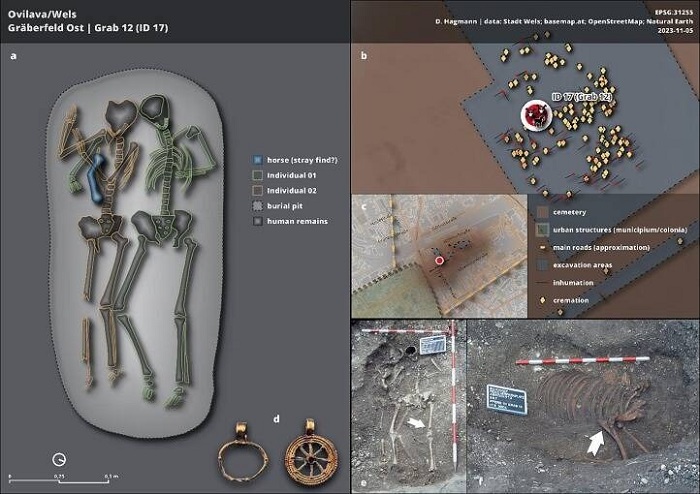

Back in 2004, construction work in Wels, Austria, revealed an unusual grave. Researchers found two skeletons, one with its arm wrapped around the other. What’s more, researchers also found that the two people were buried atop a horse.

According to a study about the skeletons just published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, researchers initially believed that they belonged to a couple, a man and a woman. They also assumed that the inclusion of the horse was indicative of “an early medieval date.”

But the new study has revealed that this interpretation was wrong. For starters, radiocarbon dating revealed that the grave was actually 500 years older than previously thought. It dated to the Roman Imperial Period instead of the Early Middle Ages. Furthermore, DNA analysis proved that the two skeletons were not a male-female couple — but mostly likely a mother and daughter.

“[A}nalysis of the human remains corrected the earlier sex assumption, revealing that the individuals were two biological females who were first-degree relatives,” the study explained. “The age difference of 15 to 25 years between the two suggests a probable mother-daughter relationship.”

The mother and daughter were also buried with grave goods: two golden pendants, one in the shape of a crescent moon, one in the shape of a wheel. These pieces of jewelry also date to the second century C.E.

So who were these two women?

Who Were The Two Women Buried In This Roman-Era Grave?

For now, little is known about the women. The daughter appeared to be between the ages of 20 and 25 when she died, while her mother was between the ages of 40 and 60. Though the daughter’s bones showed evidence of spina bifida, and the mother may have been in the early stages of osteoarthritis, researchers are unsure how they died.

“Unfortunately, we cannot say exactly how they died, but they must have died in one way or another at the same time, otherwise they could not have been buried in this way, i.e. at the same time,” study authors Dominik Hagmann and Sylvia Kirchengast told All That’s Interesting in an email. “As far as we could determine, there were no signs of violence, so they may have died of some disease or epidemic.”

The horse, for its part, appeared to between the ages of eight and nine when it died. Researchers found no sign of injury or disease and thus concluded that the horse “may have been in good health at its death.”

Such burials of humans alongside their horses are not uncommon in the archaeological record of ancient Europe. Graves of this variety have been uncovered everywhere from Germany to England within just the last several years alone.

The women and the animal lived between the second and third century C.E. in the Roman town of Ovilava. According to the study, this Roman town was near the edge of the empire’s frontiers and was an “essential economic and administrative hub… at the intersection of key Roman routes.”

It was populated mostly by civilian artisans and traders, not by soldiers, and experienced in a peak in the second century. Quite possibly, the women lived during that era. Researchers suspect that they were probably fairly well off because of the horse and the two gold pendants found in their grave.

“[The pendants] and the presence of the horse, which is not necessarily cheap to buy and maintain, probably indicate that we are not dealing with members of the poorest class,” Hagmann and Kirchengast explained to All That’s Interesting.

But though the grave offers a look at Roman funerary practices, and perhaps at familial ties during that time, questions remain. Researchers are still uncertain about the “cultural and ethnic background” of the women, the “circumstances of their death,” and the meaning of the horse.

As Hagmann and Kirchengast told All That’s Interesting, it’s even possible that a second horse was buried with the two women but, for now, the “situation is very unclear.”

Despite the questions that remain, this unique discovery is an exciting one. As the study’s authors noted, it is “the first genetically verified double burial of two first-degree relatives in ‘Roman Austria.’”