Though tens of thousands of people were crucified, just four skeletons have been found with physical evidence of crucifixion.

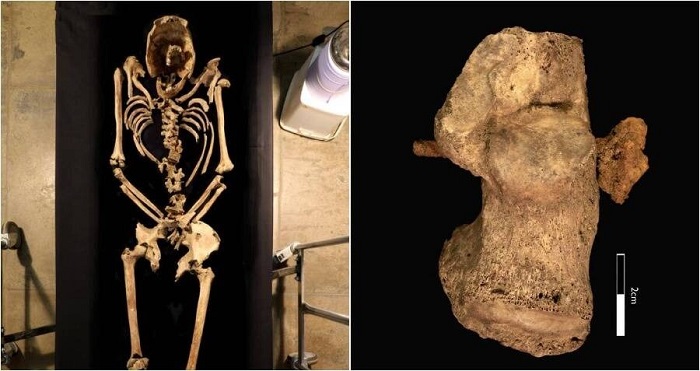

At first, the skeleton didn’t look like much. Almost 2,000 years old and caked with mud, it struck archeologists as just one of many remains found in a cluster of Roman cemeteries. But closer examination revealed an iron nail in its right heel — sure evidence of crucifixion.

“It’s essentially the first time that we’ve found physical evidence for this practice of crucifixion during an archaeological excavation,” said dig leader David Ingham of Albion Archeology.

“You just don’t find this. We have written evidence, but we almost never find physical evidence.”

Archeologists first came across the remains in 2017. While excavating land in preparations for a Cambridgeshire housing development, they found five cemeteries dating back to the 3rd or 4th century.

There, they dutifully excavated the skeleton and recorded the find. But no one noticed the nail embedded in its heel until the bones were cleaned at a nearby laboratory. Then, archeologists realized that they’d found rare, physical evidence of a Roman-era crucifixion.

“We know a reasonable amount about crucifixion; how it was practiced and where it was practiced and when and so on from historical accounts,” said Ingham. “But it’s the first tangible evidence to actually see how it worked.”

The nail in the skeleton’s heel, archeologists theorized, was to “stop him wriggling.”

According to archeologists, the skeleton belonged to a man who was between 25 and 35 years old when he died around 1,661 and 1,891 years ago. Injuries on his body, and inflammation on his legs, suggest that he was either a slave or a prisoner who spent time in shackles.

His death by crucifixion, explained Corinne Duhig, a University of Cambridge archeologist and bone specialist, shows “that the inhabitants of even this small settlement at the edge of empire could not avoid Rome’s most barbaric punishment.”

She mused that the man may have been a slave who “committed some crime or misdemeanor” or an ordinary citizen who “committed a severe crime.” Maybe, she said, he “got on the wrong side of the bosses or middlemen and was given a terrible punishment to warn others to behave.”

His death probably took between four to six days and was likely observed by Roman guards. Researchers estimate that between 100,000 to 150,000 people died by crucifixion before the practice was banned in 337 AD — but physical evidence of crucifixion is rare.

That’s because most people were affixed to crosses with ropes, not nails. And if someone was nailed to a cross, then Roman authorities often retrieved the nails after they’d died. In this case, it appears the nail bent and got stuck in the bone.

What’s more, crucifixion victims were rarely afforded a burial. Roman authorities preserved this brutal punishment for enslaved people, lower classes, or perceived enemies of the state. But this skeleton was found in a cemetery with his arms across his chest.

This, and the nail stuck in his heel, helped preserve evidence of his gruesome final moments.

To date, the skeleton found in Cambridgeshire is just one of four found with physical evidence of crucifixion. Archeologists found similar skeletons in Gavello, Italy, Mendes, Egypt, and Jerusalem, Israel. But only the skeleton found in Israel had an actual nail in it.

That skeleton, like the one found in Cambridgeshire, had a nail impaled in its heel bone. But since the body was not intact, some don’t see it as strong physical evidence that a crucifixion took place.

As such, the skeleton found in Cambridgeshire offers a rare, grisly look at capital punishment in the Roman Empire. To share this unique find, researchers hope to make a 3D replica of the bone to display at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge.

After reading about the crucified Roman-era skeleton found in England, learn about the discovery of a skeleton found in shackles from Roman-era Britain. Or, discover how scientists found the nails they believe were used to crucify Jesus Christ.