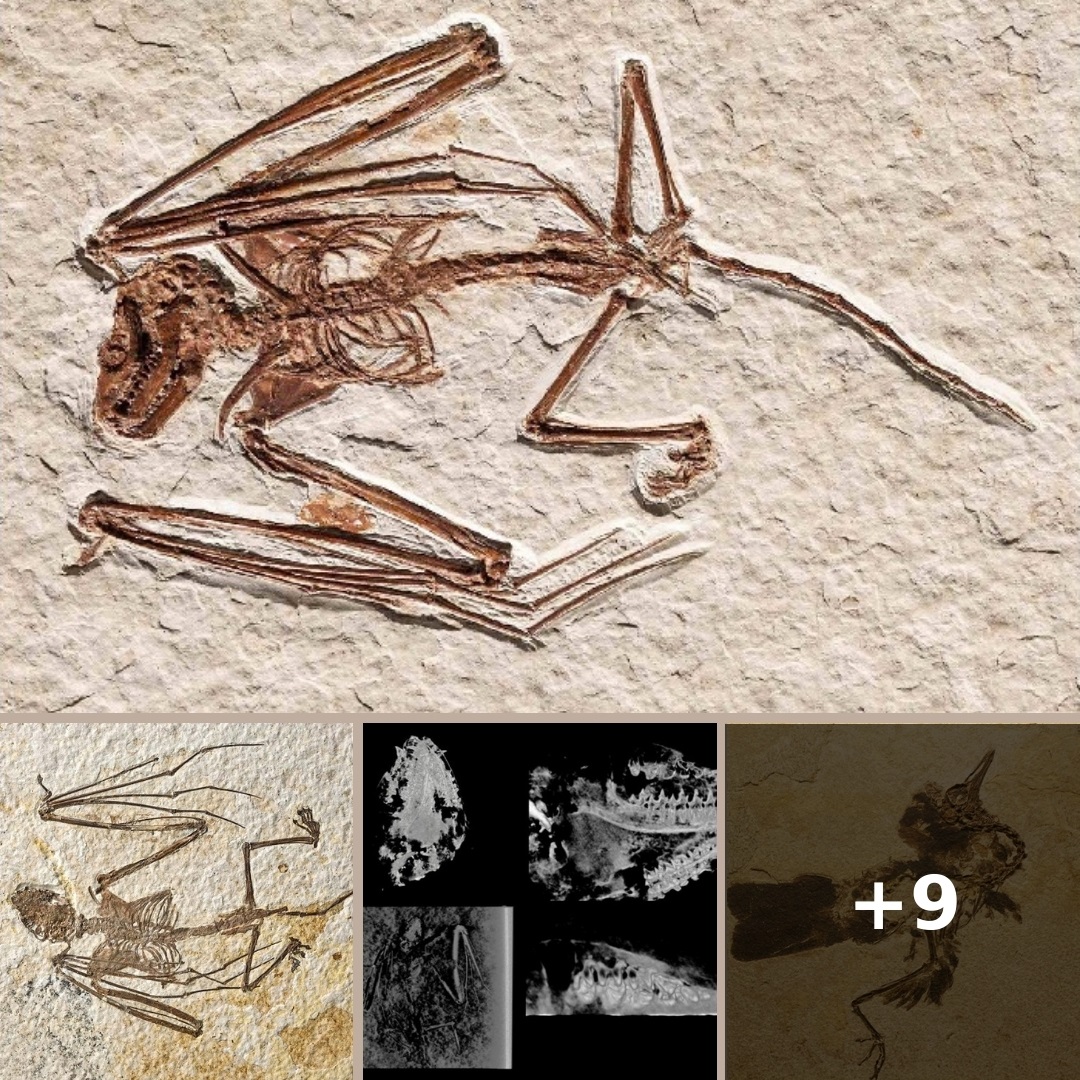

Two 52-million-year-old bat skeletons discovered in an ancient lake bed in Wyoming are the oldest bat fossils ever found – and they reveal a new species.

The world of paleontology has always been fascinating, filled with discoveries of prehistoric creatures that once roamed our planet. Recently, researchers have uncovered an incredible find – a collection of 52-million-year-old fossilized bat skeletons. Bats are fascinating creatures that have captured the imaginations of people for centuries. These creatures are masters of the night sky, effortlessly flitting through the air in search of prey using their unique echolocation abilities. These skeletons have provided valuable insights into bat evolution and have even revealed the existence of a new species. The discovery is a significant breakthrough in our understanding of these incredible creatures and their evolutionary history.

Scientists have described this new species of bat specimen as the oldest bat skeletons ever recovered. The study on this extinct paleontological specimen, which lived in Wyoming about 52 million years ago, supports the idea that bats diversified rapidly on multiple continents during this time.

There are more than 1,460 living species of bats found in nearly every part of the world, with the exception of the polar regions and a few remote islands. In the Green River Formation of Wyoming – a remarkable fossil deposit from the early Eocene – scientists have uncovered over 30 bat fossils in the last 60 years, but until now they were all thought to represent the same two species.

“Eocene bats have been known from the Green River Formation since the 1960s. But interestingly, most specimens that have come out of that formation were identified as representing a single species, Icaronycteris index, up until about 20 years ago, when a second bat species belonging to another genus was discovered,” said study co-author Nancy Simmons, curator-in-charge of the Museum’s Department of Mammalogy, who helped describe that second species in 2008. “I always suspected that there must be even more species there.”

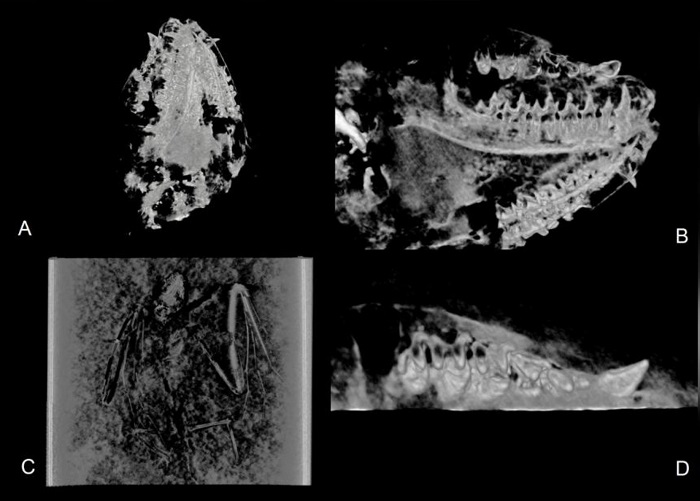

In recent years, scientists from the Naturalis Biodiversity Center started looking closely at the Icaronycteris index by collecting measurements and other data from museum specimens.

“Paleontologists have collected so many bats that have been identified as Icaronycteris index, and we wondered if there were actually multiple species among these specimens,” said Tim Rietbergen, an evolutionary biologist at Naturalis. “Then we learned about a new skeleton that diverted our attention.”

The exceptionally well-preserved skeleton was collected by a private collector in 2017 and purchased by the Museum. When researchers compared the fossil to Rietbergen’s expansive dataset, it clearly stood out as a new species. A second fossil skeleton discovered in the same quarry in 1994 and in the collections of the Royal Ontario Museum was also identified as this new species. The researchers gave these fossils the species name “Icaronycteris gunnelli” in honor of Gregg Gunnell, a Duke University paleontologist who died in 2017 and made extensive contributions to the understanding of fossil bats and evolution.

According to the researchers, the newly found Icaronycteris gunnelli was very small, weighing only around 25 grams, which is equivalent to five marbles. Despite its small size, it had already evolved the ability to fly and was likely able to use echolocation. The bat probably lived in the trees around the lake and hunted insects by flying over the water.

Matthew Jones, a researcher in the field of paleontology at Arizona State University and one of the authors of the study, suggests that bats are descendants of tiny insect-eating mammals that lived in trees. However, identifying the exact small mammal species related to bats is challenging due to the existence of numerous distinct types. In addition, most of these mammal species are familiar only through limited findings of their teeth and jaws.

The Fossil Lake deposits of the Green River Formation are considered extraordinary by experts because the paper-thin limestone layers were formed under unique conditions that effectively preserved anything that sank to the lake’s floor.

The skeletons found in Wyoming showed that they belonged to the early Eocene epoch. During this time, the Earth’s temperature was getting warmer, and animals, insects, and plants were quickly spreading and diversifying. The bats discovered in Fossil Lake are similar to the bats we have today, with long fingers used to hold their wing membranes.

The recently found bat fossils have a lot in common with modern bats but also have some distinctive features. One of these differences is that the newly discovered bat bones, particularly in their hind limbs, are much stronger and more robust. Explained Rietbergen, the lead researcher of the study.

In modern times, bats generally have thin and lightweight bones that aid in their flight abilities. However, the recently uncovered species of bat possesses thicker hind limbs, potentially suggesting that they have inherited traits from their ancestors. This implies that these bats had stronger legs to climb trees.

Furthermore, the newly discovered bat species had a claw on its index finger in addition to the thumb claw. Most bats today only have a thumb claw which helps them to hang upside down while sleeping. This new information suggests that the bats from this period could be the final phase of a transformation from climbers to expert fliers.