These researchers have made a great discovery.

Scientists claim they have finally figured out how, exactly, the Great Sphinx was built in Egypt more than 4,500 years ago.

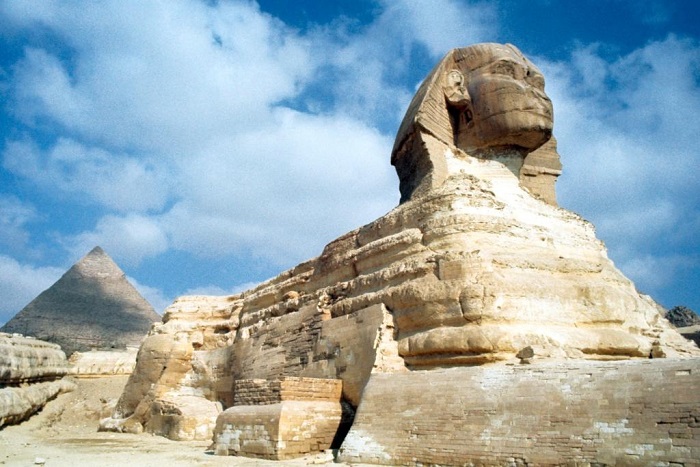

For decades, experts have agreed that the detailed face of the iconic limestone statue found along the Nile River in Giza was most likely hand-carved by stone masons — but they have never concluded how the massive, layered body was created in the first place.

A study conducted by researchers at New York University, which has been accepted for publication in the journal Physical Review Fluids, posited that erosion can create Sphinx-like shapes.

“Our findings offer a possible ‘origin story’ for how Sphinx-like formations can come about from erosion,” Leif Ristroph, senior author of the study, said in a statement.

“Our laboratory experiments showed that surprisingly Sphinx-like shapes can, in fact, come from materials being eroded by fast flows.”

This not only means that nature had a role in creating the colossal statue but the formation may have actually inspired Egyptians to turn it into a statue in the first place.

“These results show what ancient peoples may have encountered in the deserts of Egypt and why they envisioned a fantastic creature,” Ristroph and his team wrote.

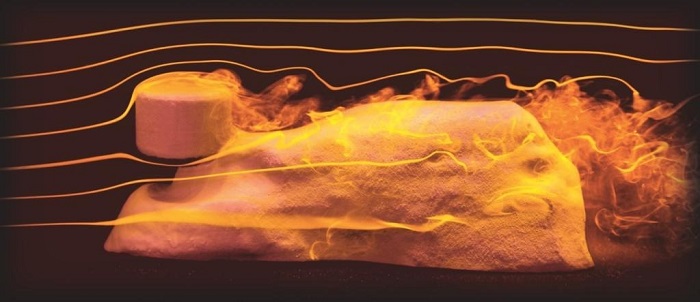

To test their theory, the team analyzed how wind creates and moves against unusual rock formations, called yardangs, found in deserts.

The researchers took mounds of soft clay with harder, less erodible material embedded inside to replicate the terrain in northeastern Egypt and then washed these formations with a fast-flowing stream of water to act as the wind.

In the end, the clay eventually resembled a Sphinx-like formation which was subsequently detailed by humans.

The Great Sphinx is believed to be a manifestation of the sun god, built to protect the pyramids around 2500 B.C., during the 4th dynasty, along with the Great Pyramids of Giza.

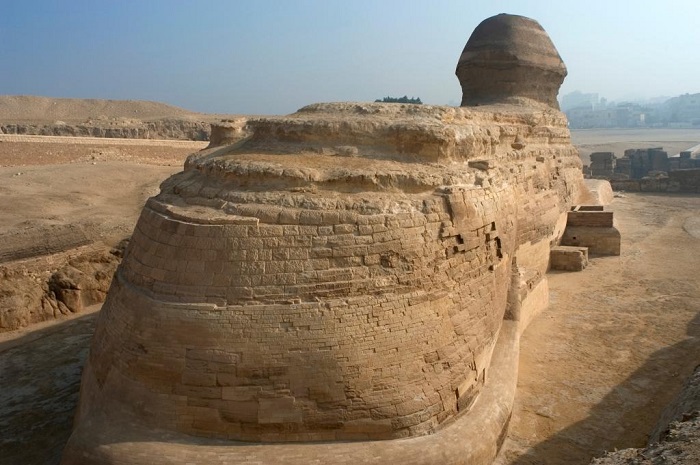

The experiment tested a theory initially proposed in 1981 by geologist Farouk El-Baz, who claimed the Great Sphinx was naturally created by wind eroding the sand.

NYU’s experiment to re-create a yardang resulted in a lion’s “head,” an undercut “neck,” “paws” laid out in front on the ground and an arched “back.”

“There are, in fact, yardangs in existence today that look like seated or lying animals, lending support to our conclusions,” Ristroph said.

“The work may also be useful to geologists as it reveals factors that affect rock formations — namely, that they are not homogeneous or uniform in composition,” Ristroph added.

“The unexpected shapes come from how the flows are diverted around the harder or less-erodible parts.”