It’s a “titanic” treasure trove.

A veritable “Holy Grail” shipwreck said to be worth billions could be exhumed from the depths of Colombia as early as next month, sparking a veritable gold rush in archeological circles, experts say.

“There has been this persistent view of the galleon as a treasure trove,” lhena Caicedo, director of the Colombian Institute of Anthropology and History, told the Guardian.

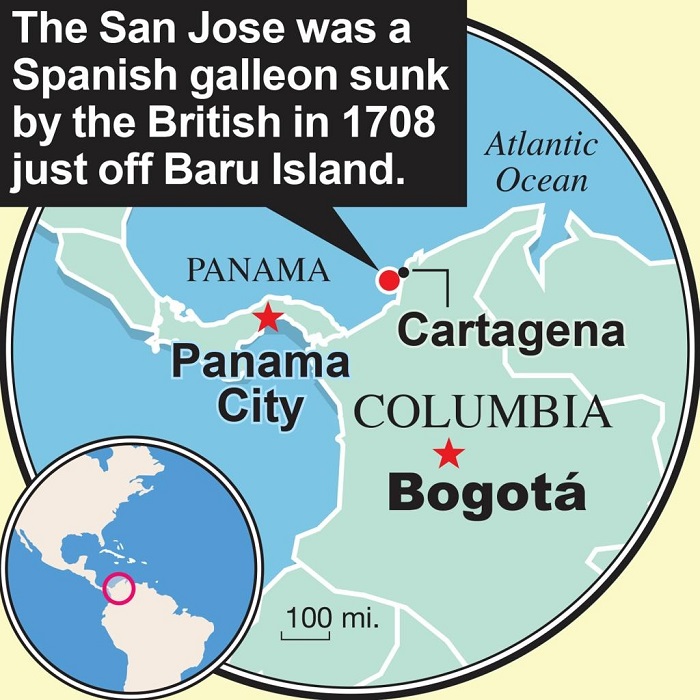

For the uninitiated, the San José galleon was the pride of Spain’s treasure fleet which was sunk off Baru Island, Cartagena in 1708 during the war of Spanish Succession, whereupon it lay undiscovered until 2015.

It was notable for its record-breaking cache of emerald, gold and silver whose total value is estimated at a cool $17 billion.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the ownership of the 131-foot vessel has been fiercely disputed with Spain, Colombia, Bolivian indigenous groups, and even the US laying claim to this holy grail of the high seas.

Now, authorities claim that they’re setting politics aside and are planning to salvage the San José’s artifacts starting in April.

“We aren’t thinking about treasure,” said Caicedo.

“We’re thinking about how to access the historical and archeological information at the site.”

She and other historians specifically hope that the shipwreck will provide them with valuable insight into the Spanish empire at its zenith of power — as well as their involvement in Latin America.

“There are so many questions the San José could help answer!” said Ann Coats, an associate professor of maritime heritage at the University of Portsmouth in the UK.

Then, seemingly echoing the motto of fictional archaeologist Indiana Jones, Caicedo and others hope to raise the galleon to the surface and display it in a museum for all to see.

This project will be easier said than done. Not many vessels like the San José have ever been recovered while zero have been salvaged from tropical waters.

“This is a huge challenge and it is not a project that has a lot of precedents,” declared Caicedo, who sees her team as “pioneers” in this regard.

The biggest challenge will be getting the 316-year-old wreck and its precious payload to the surface without it disintegrating.

“The contents are really varied and we have no idea how the remains will react when they come into contact with oxygen,” said Caicedo. “We don’t even know if it is possible to raise something out of the water.”

Not to mention that the 60-gun ship was set alight before it sank, which could’ve further compromised its structural integrity.

Part of the challenge is that the San José — whose exact coordinates have been kept a secret by the Colombian government to prevent looting — is located 2,000 down, making it impossible for divers to access.

In accordance, Colombia’s military is currently developing state-of-the-art salvage robots.

These automated submersibles will be tasked with retrieving the items — an operation that will cost more than $4.5 million, CBS reported.

Culture Minister Juan David Correa said the bots would initially gather items from the San José’s surface to see “how they materialize” when brought to the surface.

This dry run would hopefully provide valuable insight into how to “recover the rest of the treasures,” he said.

In 2017, the world got a teaser of the treasure that lies beneath after the Colombian Navy dispatched a remotely operated vehicle down to 3,100 feet to survey the wreckage. The resultant footage depicted gold pieces, cannons, fine china, swords and clay vessels scattered across the ship.

This latest expedition would reportedly be the biggest, most expensive and most complicated underwater recovery mission in history.

It also marks a watershed moment for historians, whose salvage efforts were until now hamstrung by intense legal battles over who was the rightful owner.

While the wreck was discovered in Colombian waters, Spain initially insisted that the San José belonged to them given that it was a Spanish flagship.

This was disputed by Bolivia’s indigenous communities, who lay claim to the treasures on the grounds that their ancestors mined them for the Spanish empire.

Meanwhile, US salvage company Sea Search Armada, which claims they discovered the ship in 1981, said that the Colombians agreed to split the profits in exchange for the coordinates.

In 2011, a US court ruled that the San José was the property of Colombia.

“It would be nice if for once money wasn’t driving things and a huge cultural collaboration could take place to study it properly,” said Coats.