Researchers have discovered cutmarks around cancerous lesions on a 4,000-year-old Egyptian skull that suggest ancient Egyptian doctors may have attempted a surgical remedy for malignant tumors.

We know from ancient papyri that even 4,000 years ago Egypt had advanced knowledge of anatomy and physiology, and thanks to their medical and mummification practices, their surgical know-how was also advanced compared to other ancient cultures. They did not have a full understanding of cancer as we know it. There are references to tumors and “eating lesions” with suggested treatments in the texts, and evidence of malignancy in human remains. Given Egyptian expertise, it stands to reason that they may have explored surgical solutions to excise a malignant tumor.

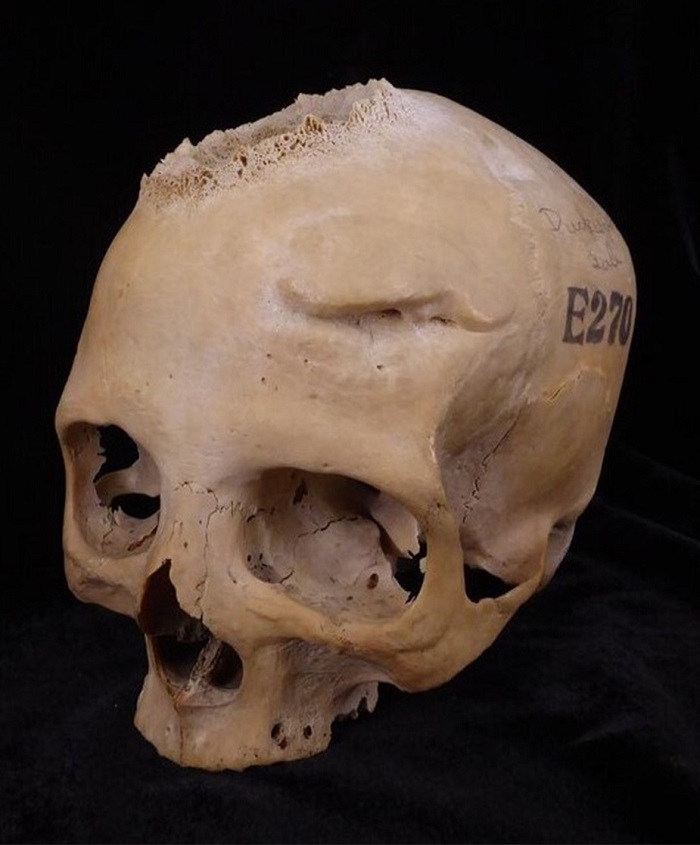

To explore ancient Egyptian knowledge and treatment of tumors, researchers took a closer look at two skulls in Cambridge University’s Duckworth Collection from different dynasties with different conditions. Skull E270 dates to the Late Period (664–343 B.C.) and belonged to a woman older than 50 when she died. The skull shows evidence of one primary tumor and several healed cranial fractures. Skull 236 dates to the Old Kingdom (2,687–2,345 B.C.) and belonged to a man between 30 and 35 years of age. It reveals evidence of two tumors and is one of the oldest cases of malignancy known.

Microscopic examination of Skull 236 found a large lesion with associated tissue destruction (neoplasm), plus about 30 small round lesions from metastasis. The surprise discovery were cutmarks made repeatedly around the lesions that were inflicted near the time of death (perimortem), not during mummification.

[A]lthough neoplasms were a clear medical frontier, skull 236 reveals new insights on a potential exploratory phase amongst medical practise concerning neoplastic lesions. As seen, reliable perimortem cutmarks on the bone surface have been identified in clear association with the metastatic lesions on the posterior cranial region. The position of the marks, running through two of the lesions with a clear associated start and end at both sides of the lytic lesions (stopped by the margins of the pathologies), suggest some kind of perimortem anthropic intervention given that they were generated on a bone in fresh condition. Although this might indicate medical surgical exploration or an attempt of care or treatment, our study has a clear limitation in the identification of the timing of the cutting. Although they are perimortem, they might also indicate a postmortem manipulation of the corpse. In turn, this might also indicate a postmortem exploration of the tumoural pathology.