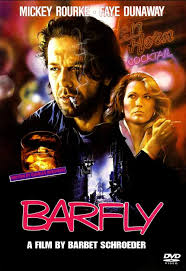

is a raw, grimy, and strangely poetic character study rooted in the semi-autobiographical world of poet and novelist Charles Bukowski. Directed by Barbet Schroeder and written by Bukowski himself, the film stars Mickey Rourke as Henry Chinaski, Bukowski’s infamous alter ego—a down-and-out writer who spends most of his life in seedy bars, drinking, brawling, and spitting out words between shots of whiskey.

What sets Barfly apart is not just its commitment to portraying the skid row lifestyle, but its refusal to romanticize it. The film dives headfirst into the neon-lit world of dive bars, drunken arguments, and existential musings. Rourke’s Henry is not a lovable loser in the traditional sense. He’s abrasive, cynical, often self-destructive, yet curiously compelling. His poetry flows from the gutter, and his worldview is filtered through alcohol and brutal honesty.

Faye Dunaway plays Wanda Wilcox, a kindred spirit to Henry—a fellow alcoholic who becomes his lover and drinking partner. Dunaway brings a strange grace to Wanda, adding depth to a character who could have easily been reduced to a tragic cliché. Their relationship is toxic yet tender, fueled by mutual understanding and shared despair.

Rourke’s performance is eccentric, some might say divisive—he slurs, stumbles, and swaggers through scenes in a performance that’s part impersonation, part incarnation. It’s not realism in the traditional sense, but something more theatrical and haunted, echoing the poetic absurdity of Bukowski’s writing.

Shot in worn-down corners of Los Angeles, Barfly oozes atmosphere. It captures a very specific kind of loneliness and defiance, where people live not to succeed, but to endure. It’s funny in the darkest way, tragic in its beauty, and unsentimental to its core.

More than just a portrait of a drunk writer, Barfly is about living outside the system, refusing to conform, and finding strange comfort in society’s margins. It’s grimy, yes—but in its grime, it finds a kind of weird transcendence. For those willing to sit at the bar with Henry Chinaski, it offers a wry, unfiltered glimpse into the soul of a man who’d rather write about life than fix it.